Last week we talked about the importance of livestock management in the battle against climate change. It came as a real revelation to this city girl that large grazing animals are a vital and necessary part of the solution to climate change. Sheep can actually help to improve soils, which improves the soil’s ability to absorb water and maintain its original nutrient balance – and most importantly, by increasing the organic matter in the soil, it makes the soil a highly effective carbon bank.

So the management of the livestock can be beneficial – but it’s a long way from a sheep in the pasture to a wool fabric. So let’s look at the wool produced by these sheep and examine what “organic wool” means.

In order for wool to be certified organic in the U.S., it must be produced in accordance with federal standards for organic livestock production, which are:

- Feed and forage used for the sheep from the last third of gestation must be certified organic.

- Synthetic hormones and genetic engineering of the sheep is prohibited.

- Use of synthetic pesticides on pastureland is prohibited and the sheep cannot be treated with parasiticides, which can be toxic to both the sheep and the people exposed to them.

- Good cultural and management practices of livestock must be used.

A key point to remember about the USDA and OTA organic wool designations: the organic certification extends only to livestock – it doesn’t cover the further processing of the raw wool. Should that be a concern?

Wool as shorn from the sheep is known as greasy (or raw) wool. Before it is suitable for further processing it must be washed to remove dirt, water soluble contaminants (called suint), and woolgrease – and there are a lot of these contaminants. On average, each ton of greasy wool contains:

- 150 KG woolgrease (when refined this is known as lanolin)

- 40 KG suint

- 150 KG dirt

- 20 KG vegetable matter

- 640 KG wool fiber

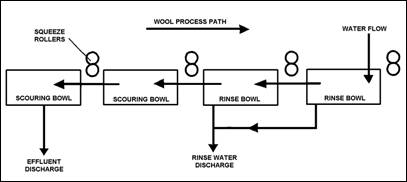

This process of washing the wool is known as scouring. Scouring uses lots of water and energy :

- water for washing: The traditional method of wool scouring uses large amounts of water to wash the wool – the wool is passed through a series of 4 – 8 wash tanks (bowls), each followed by a squeeze to remove excess water. Typical scouring plants can consume up to half a million litres of water per day.

- pollution: The scouring water uses detergents and other chemicals in order to remove contaminants in the greasy wool, which creates the problem of disposing of the waste water without contaminating the environment. In unmodified plants, a single scouring line produces a pollution load equivalent to the pollution produced by 30,000 people.[1]

- energy: to power the scouring line.

What about the chemicals used?

Detergents used in wool scouring include alkylphenol ethoxylates (APEOs) or fatty alcohol ethoxylates (more benign); sodium carbonate (soda ash), sodium chloride and sodium sulphate. APEOs are among those chemicals known as endocrine disruptors – they interfere with the body’s endocrine system They’re known to be very toxic for aquatic life – they cause feminization of male fish, for example. (Click here to see what happened to alligators in Florida’s Lake Apopka as a result of endocrine disruptors traced to effluents from a textile mill. ) More importantly they break down in the environment into other substances which are much more potent than the parent compound. They’re banned in Europe.

The surface of wool fibers are covered by small barbed scales. These are the reason that untreated wool itches when worn next to skin. So the next step is to remove the scales, which also shrinkproofs the wool. Shrinking/descaling is done using a chlorine pretreatment sometimes combined with a thin polymer coating. (Fleece is soaked in tertiary amyl or butyl hypochlorite in solution and heated to 104° for one hour. The wool absorbs 1.5% of the chlorine. [2] ) These treatments make wool fibers smooth and allow them to slide against each other without interlocking. This also makes the wool feel comfortable and not itchy.

Unfortunately, this process results in wastewater with unacceptably high levels of adsorbable organohalogens (AOX) – toxins created when chlorine reacts with available carbon-based compounds. Dioxins, a group of AOX, are one of the most toxic known substances. They can be deadly to humans at levels below 1 part per trillion. Because the wastewater from the wool chlorination process contains chemicals of environmental concern, it is not accepted by water treatment facilities in the United States. Therefore all chlorinated wool is processed in other countries, then imported.[3] (For more about chlorine, go to the nonprofit research group Environmental Working Groups report about chlorine, http://www.ewg.org/reports/considerthesource.) There are new chlorine free shrink/descaling processes coming on the market, but they’re still rare.

Finally, there is the weaving of the yarn into fabric – and all the environmental problems associated with conventional weaving and finishing. In addition to the environmental concerns associated with conventional weaving, dyeing, and finishing (see some of our earlier blog posts), wool is often treated for moth and beetle protection, using pyrethroids, chlorinated sulphonamide derivatives, biphenyl ether or urea derivatives, which cause neutrotoxic effects in humans.

In the last 10 years, the textile industry, along with animal ethics groups like People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, have lobbied against the wool industry, taking a stand against unethical treatment of sheep. In 2004, U.S. retailer Abercrombie and Fitch became the first to sign on to an animal rights campaign boycott of Australian wool that stood firmly against the typical practices of mulesing (where folds of skin around the sheep’s anus are cut off with shears during the wool shearing) and live export of sheep to halal butchers when their wool production becomes minimal. Other companies such as H&M, Marks & Spencer, Nike, Gap, Timberland, and Adidas (among others) have since joined, sourcing wool from South Africa or South America (where mulesing is not done). The result of this outcry has led to the increased production of both organic and ethical wool, though it is still relatively minor when compared to the overall global wool production.

To complicate things a bit more, each country maintains their own standards for “organic wool” – Australia, for instance, has no equivalence or agreement with US organic standards. The International Wool Textile Organization (IWTO) has adopted a new organic wool standard (closely aligned with GOTS) which they hope will be accepted by its members. In addition, many companies use the term “eco wool”, which means the wool is sheared from free range roaming sheep that have not been subjected to toxic flea dipping, and the fleece was not treated with chemicals, dyes or bleaches – but this is wide open to interpretation and exploitation. According to the IWTO, “Eco wool” must meet the standards set by the EU Eco-label.

Wool is a fabulous fiber – in addition to its many other attributes, it smolders rather than burns, and tends to be self-extinguishing. (Read what The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CISRO), Australia’s national science agency, has to say about the flame resistance of wool by clicking here: http://www.csiro.au/files/files/p9z9.pdf ) So if you can find organic wool – making sure, of course, that the term “organic” covers:

- management of the livestock according to organic or holistic management principles

- processing of the raw wool, using newer, more benign processes rather than harmful scouring and descaling chemicals; and wastewater treatment from scouring and processing

- weaving according to Global Organic Textile Standards (GOTS). Read more about GOTS here.

…then go for it! Nothing is quite like it in terms of comfort, resilience, versatility and durability.

But first you have to find it. And that means you’ll have to ask lots of questions because there are lots of certifications to hide behind.

[1]The Cleanier Production Case Studies Directory EnviroNET Australia, Environment Protection Group, November 1998

[2] “Textiles: Shrink-proof wool”, Time, October 17, 1938

[3] “Fabric: Chlorine Free Wool”, Patagonia website, http://www.patagonia.com/web/us/patagonia.go?slc=en_US&sct=US&assetid=8516

Your blog is amazingly informative and in-depth. Wonderful work.

Thanks so much Armeen. We love pats on the back. Leigh Anne

Where can one buy men’s organic wool or shearling gloves?

So sorry – we just point out the issues, we don’t necessarily know where to buy products!

Hi,

Thanks for trying to spread the word about the descaling process. “Superwash” is very popular in the states. As a small farm/mill using only local fiber we cringe everytime we see so called “indy dyers” promoting superwash yarn as something they make. So much of the yarn being sold in the U.S. and being marketed as handmade is just imported yarn that is then dyed here. Please continue your good efforts!

I’m looking for very clean wool for my baby that was ethically raised and made. Thank you so much for addressing every ethical issue in the process of getting wool ready to put on the market. Can you suggest websites to purchase it from that keep it good and clean every step of the way?

Hi Marcia: I’m afraid I don’t know of any retail websites which have wool for sale, but I do know that knitters are passionate about the craft and love their wool! Perhaps there are some websites which have forums where you can ask this question? My answer will always be the same, when looking for any organic product – first, look for the certifications. A company which has invested the (considerable) time and money into a certification will surely have that information available for their products. And remember for wool it’s the same as for other fibers – there are certifications for the fiber, and also for the processing. So if you find organic wool it’s important to ask whether the processing was also certified. The best would be to find GOTS certified wool products. But it’s also true that these certifications cost quite a bit of money, and for smaller companies, especially, that could mean a hardship. So if you find a company that you trust to provide a safe, ethically raised product for your baby, listen to your heart.

Great article – thanks!

Hi, how about ecobaby? Is there wool in crib mattresses considered safe?

I’m afraid I don’t keep up with all the retailers. You can ask them if the wool they use is GOTS certified – which would mean it’s organic wool, minimally processed. That would be the best. If it’s Oeko Tex certified, they wouldn’t have had to use organic wool.

Thank you so much for this information!

I recently decided to start spinning my own yarn and I have been meaning to find out what superwash means. Sounds good when you have no idea what it actually is. That is disgusting! I am so glad to have found this site! I will ask for now on plenty of questions before I buy any more roving or yarn. I had no idea how terrible most yarn is on the planet. I am a very eco friendly, no pesticide wanting person. So thank you for all this information. It is very helpful.

“The surface of wool fibers are covered by small barbed scales. These are the reason that untreated wool itches when worn next to skin.”

Just want to mention as politely as possible that this is inaccurate. The cut ends of the fibers are what causes irritation. Envision you are walking through a freshly mowed lawn, and the flower stalks on the grass are poking your bare feet, but when the grass is laid on its side, you feel no discomfort. Basically, this is the same cause and effect.

Some breeds have more open scale structure which causes, in my opinion, a very unpleasant sensation in the hand. It feels sort of dead and dry, and almost gritty in comparison to a buttery, vibrant, rose petal texture that is much more desirable. I focus on more closed-scale structure in my breeding programs.

I will never wear, nor support superwash fibers. As a producer of premium fibers, a fiber artist, a proud wearer of wool and a man- I don’t see what is so hard about washing woolens in cool water and laying them out to dry. If I can wash a wool sweater, anyone can! 🙂

Thank you for the mention on how grazing flocks and herds are beneficial to the environment. We producers are under the knife by radicals on many fronts. We dedicate the greater parts of our lives to the health and future of our families, range, wildlife and livestock. It is refreshing to read an article that is not attacking us. Bless you!

Thanks so much for your explanation. As we say often, we’re not fiber chemists and have a lot to learn. I love your “buttery, vibrant, rose petal texture” description – makes me want to run out and buy some lovely organic wool!

Hello Croesoacolorado,

I love your post/comment above, I would love to learn more about what you do exactly, You menioned you are a premium fiber producer. I am looking for interesting materials for a menswear collection I am working on. I typically don’t post my email, but I would love to get in touch with you, my email is: Thebravowaynyc@gmail.com. If you would be so kind to email me, I would be very grateful. Thank you!